The Home Stretch

By the end of the 1980s, it felt like analog synthesizers were done. Over. At the time, the idea of anyone still playing a Sequential Circuits instrument decades later seemed almost ludicrous. But by the time Evolver appeared in 2002, that had changed. People valued vintage synthesizers less for their ability to emulate other instruments and more for their inherent sound, their unique “voice.” I can’t say that this change in attitude had a dramatic impact on the way the new instruments were designed. The goal is always to make a great musical instrument. But there is an awareness now that musicians are making choices less because an instrument is the next big thing and more because the experience of playing that instrument is satisfying and inspirational. In other words, more musical. As to what makes an instrument great, that’s complicated and maybe a subject for another, separate discussion. I will say that I think sales numbers are not necessarily an indication of greatness, or the only indication, anyway. And greatness can be very subjective.

As far as I’m aware, the Prophet-6 is still the second best-selling DSI/Sequential synth. (The Prophet Rev2 is first. If you consider the Rev2 an updated Prophet ’08—which it is—the combined sales numbers exceed any of the other synths by a large margin.) I was never overly optimistic about sales of any of the synths. I never thought, Oh, this is going to sell really well. The Prophet-6 was different. Yes, it “checked a lot of boxes,” but it instantly felt comfortable to me, and it sounded great. Any reservations I had about the limitations or the vintage-style interface quickly evaporated. It felt like any depth of function that was sacrificed was more than made up for by the immediacy and the joy of playing it. It felt like a musical instrument. And it was nice to be reminded of just how versatile a synth like that can be despite any perceived limitations. Maybe most importantly for me, the Prophet-6 made me rethink the musician/instrument interface in a way that greatly affected subsequent, more original designs. This is most evident in Take 5, which strikes a balance between a knob-per-function, live-panel interface and a deeper, menu-driven functionality that, while not hidden, stays out of the way for most interactions not directly related to playing, performance, and basic sound design. The synth provides immediate visual feedback for the foundational parameters while also allowing deep dives.

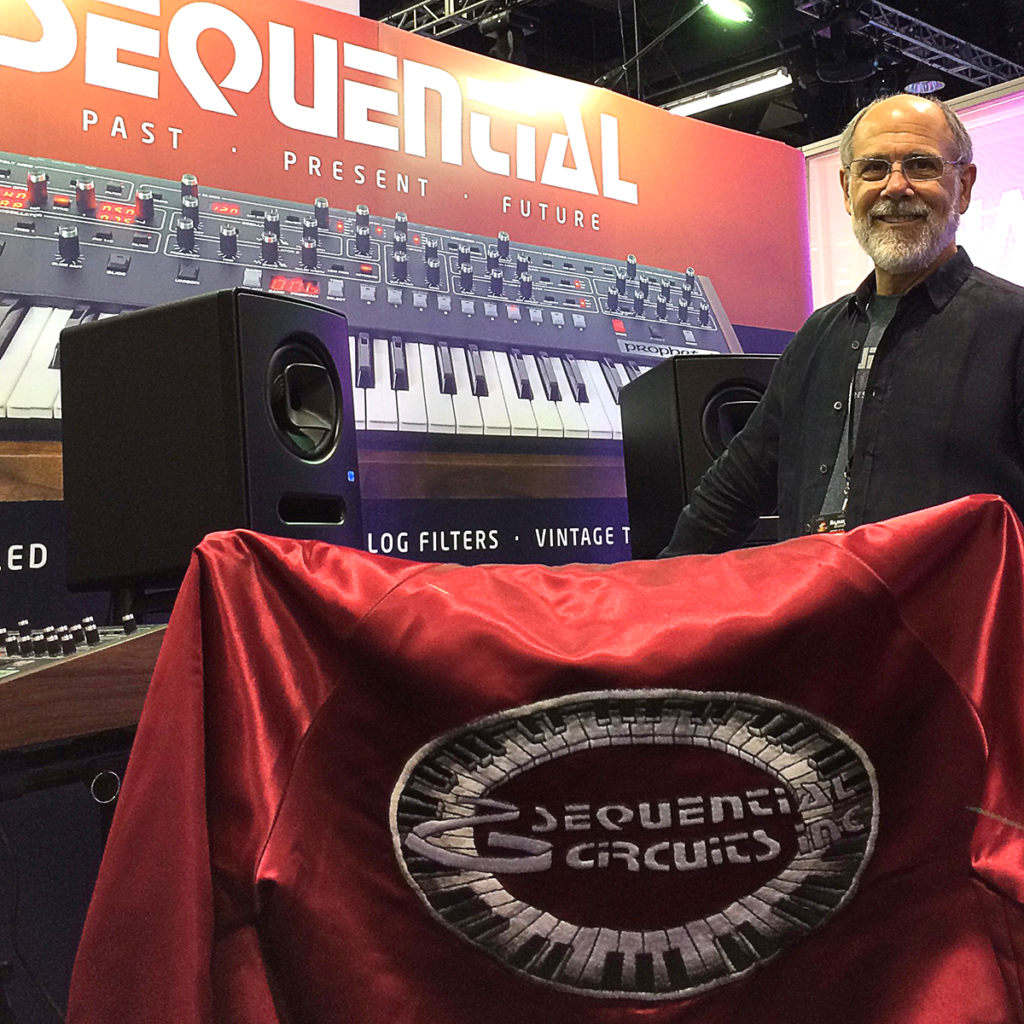

People were caught off guard by the introduction at NAMM in January 2015. The reaction was overwhelmingly positive and presales were strong, but the Prophet-6 was still far from production-ready. There’s an old joke that NAMM really stands for “not available, maybe March?” Or is it May? The point is, just because a product is announced and appears functional, it may not be ready for the world outside the Anaheim Convention Center. In addition to the alpha-to-beta mechanical and hardware changes already mentioned, there is always hardware fine-tuning to be done, like tweaking of signal levels and ranges. On the software side, the OS needs to be made feature complete and bugs need squashing. Ideally, that happens before sound design begins, but that is often not the case, so patches need to be tweaked, maybe more than once. The operation manual needs to be written, illustrated, laid out, edited, and—in those days, still—printed. There is testing, testing, and more testing. Packaging needs to be designed and samples approved. And as everything gets nailed down, parts have to be purchased from domestic and international vendors to show up at more or less the same time so that everything can be manufactured and assembled. In parallel, orders continue to be taken. The always looming question of “How many of these are we going to make?” must be answered and allocations considered. And then, finally, there’s a preproduction run and a “golden sample” and, barring any last-minute, hopefully minor tweaks, actual production begins. That all of this was accomplished start to finish in roughly a year seems miraculous to me now.