The Game Is Afoot

I never really had a job title until I needed one for the company’s acquisition by Focusrite: Senior Product Designer. As titles go, it’s okay, I suppose, and generally describes my role. (My first Dave Smith Instruments business card gives my title as The Other Guy, as in, “Dave and the other guy.”) I did occasionally think that if I ever wanted to work somewhere else, having an important-sounding job title might be helpful, but as it turns out, that wasn’t necessary. I just kept doing what I did until I didn’t anymore.

DSI had a pretty unique way of developing products. We never had a shortage of product ideas, so the first step was to decide which of them we wanted to tackle next. That decision was not driven by Marketing or the vagaries of the synthesizer market—Dave generally thought Marketing was a waste of time and money—but rather by what seemed interesting to us. After all, we were all synth dorks, so if we thought something was interesting, the odds were very good that other people would, too. And if we did a good job, we would sell enough of that instrument to allow us to make another one. That was all we really cared about. Gradual growth and products that continued to sell over a period of years were more important than maximizing sell-through and then scrambling to come up with the next thing.

The Prophet-6 was a bit unusual in that we had a solid idea of what it was and what it looked like and the awareness that, if we didn’t screw it up, it was going to sell well, but the process was still the same. Typically, we didn’t write specs. We drew pictures, starting with the front panel. (The one exception to this was Tempest, for which Roger Linn created a lot of preliminary documentation.) Most instruments started with whiteboard drawings before moving into Adobe Illustrator, but I don’t recall much time being spent at the whiteboard for the Prophet-6. We knew the general size and shape. The length was determined by the 4-octave keyboard plus a wheelbox and we wanted to limit the width (front to back) to keep the instrument to a size that was easily portable and didn’t take up a lot of room. We wanted to avoid adding a spacer at the right end of the keyboard to increase the length and gain additional panel real estate. (At the time, we were getting a lot of feedback from customers about space limitations in their workspaces.)

I started by doing some preliminary mechanical design to better determine the actual dimensions. When I first started working at DSI, all the drawings—panel graphics, screen-printing art, and the mechanical design—were done in Adobe Illustrator. I don’t know why. Maybe Dave already had a copy when he started working on Evolver. Maybe he knew someone and got it cheap. He needed Illustrator or something like it for the graphics, so maybe he just thought, why learn Illustrator and some CAD software when I can do everything in Illustrator? (Evolver was Dave’s first solo synth design in a long time and things had changed greatly in the intervening years, largely due to the advent of personal computers.) In any case, that was fine with me, because I was already familiar with Illustrator from my time as a technical writer. The tools are not great for mechanical drawing, but you can do parametric entry and snap to grids, so it’s workable.

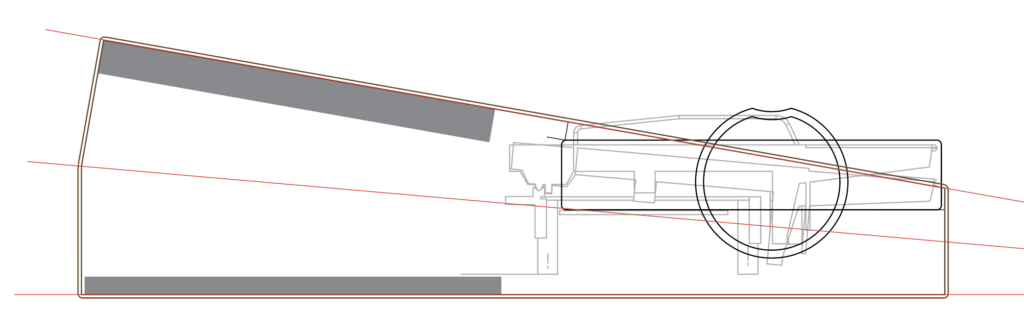

When I first started at DSI, the 2D Illustrator drawings would be given to the metal and wood vendors who would then build 3D drawings in SolidWorks. I did gradually transition to working in 3D—the Prophet 12 module was the first complete product I modelled—but I started sketching the Prophet-6 in Illustrator before moving over to the CAD software. I had 2D drawings of the 4-octave, Fatar keyboard and the pitch and mod wheel assembly, so I drew a profile view from the right side from which I could derive the useable width, meaning the area of the panel in which the panel PCBs would fit without running into obstructions like the rear of the keys. So, I had a realistic estimate of the length and width to use as a starting point for the panel layout. (A note on terminology: Though it’s common to describe the end-to-end dimension of a keyboard as its width, length is, by definition, the longest dimension of an object, so width in this case refers to the front-to-back dimension and length is end to end.)

I didn’t have to give much thought to graphic design because the “rules” had already been established by Dave when he designed the Prophet-5. White-on-black screen printing with “modules” bounded by borders with rounded corners, and Eurostile for the typeface. (The Prophet-5 typeface was Microgramma. Eurostile is a very commonly used digital typeface and essentially an updated version of Microgramma.) Dave would have laid out the Prophet-5 panel art by hand using dry transfer lettering, lines, and corners—probably on some sort of graph paper—which was then photographically reduced to make the screens for silkscreen printing. Creating the graphics in Illustrator is faster, more editable, and more accurate. Computers for the win! The screen printing for production is still done by hand, just as it was in “the old days.” Industrial screen printing is becoming something of a lost art. I put a lot of effort into qualifying vendors for production, especially for instruments like the Pro 3 SE. The Prophet-6 was relatively simple and just two ink colors.

The panel was smaller than the Prophet-5’s with more knobs and switches, so I used a 20-lines-per-inch (.05″) grid to give me flexibility while also adhering to a grid. I think I remember from laying out the Prophet-5 Rev 4 panel that it was on a .125″ grid. Bigger panel; fewer controls. I can’t recall if I did this on the Prophet-6, but I sometimes went “off grid” when it felt right. I feel that the layout of a musical instrument can be too rigid, especially one with a lot of UI elements. It’s beneficial—maybe even more musical, in a way—to be able to identify different sections of the UI based solely upon the pattern or arrangement of the controls. (Am I getting too “inside baseball?”)

The first layout went relatively quickly. As always happens, there were some surprises. I had trouble getting things to fit with individual waveshape switches à la the Prophet-5, so I changed it to a knob that swept continuously from triangle to sawtooth to pulse waves. That meant, unlike the Prophet-5, each of the 3 waveshapes was available on both oscillators and an additional destination switch would enable waveshape to be modulated via Poly Mod. It also meant, as John Bowen would find out when trying to recreate the 40 original Prophet-5 programs on the Prophet-6, one or two of the original factory presets couldn’t be replicated exactly because that combination of waveshapes was not available using the knob. I was more than willing to make that trade.

As often happened when laying out a panel, there was an odd space that wasn’t easy to get rid of by simply shuffling things around. (This is preferable to running out of space before everything is placed on the panel, however.) To fill the space, I added a very rudimentary step sequencer, just Record and Play switches.

You might ask, how could there be no room for the waveshape switches and extra, unfilled space? The user interfaces of integrated or “slab” synths typically group controls into modules of related parameters, so much of the layout process involves not just moving individual controls, but groups of controls. It’s a bit like a (very slow) game of Tetris where you’re trying to make things fit together as seamlessly as possible without any gaps. Layout generally requires a lot of thought and multiple iterations before arriving at something that looks and feels right, and—in some cases—elements need to be added or removed or combined into a single control to make it work. (One of my least favorite tasks as a designer was laboring intensely for months over the layout of a keyboard instrument and then having to change and adapt that layout relatively quickly for a desktop module. I rarely felt completely satisfied with the results. The two exceptions are the Prophet Rev2 and OB-X8 modules, the latter with the capable assistance of Carson Day.)