Tom

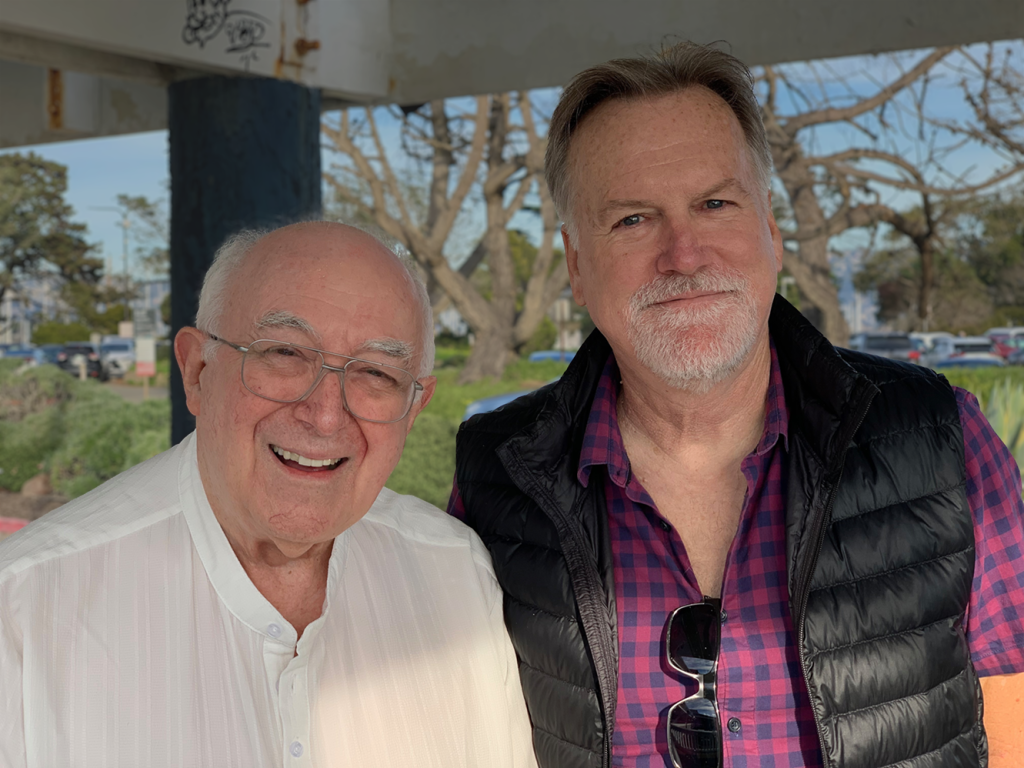

I was sitting in my office at Seer Systems one day in 1997 or thereabouts when the phone on my desk rang. It was Dave Smith calling from his home. “I’ve been talking to Tom Oberheim. He’s between jobs and wants to learn about software synths, so I asked him if he wanted to write the Reality operation manual. Can you get him set up and manage that?” I knew who Tom was, of course, but I had never met him, and now Dave was asking me to be his manager. I had no reason to believe that Tom was anything other than the warm, bright, and kind person that I now know he is, but the idea that I would be managing him made me deeply uncomfortable.

Seer Systems was in the process of developing Reality, which is generally considered to be the first “professional” software synthesizer, though I’m not certain what makes one synthesizer professional and another not. Seer was a seriously engineer-heavy company and, being not an engineer, I had fallen into what would become my customary role: doing the things nobody else had the desire or the time or simply the experience to do. (It didn’t seem to matter that I might not have had whatever experience might be necessary.) I designed, built, and maintained the website. I managed the design of the packaging and wrote copy. (Once upon a time, you bought software on physical media from actual stores!) I acquired the raw sample data from various sources and managed the editing process, including quality assurance. I configured and purchased PCs for development. I oversaw sound design and the creation of demos. I did lots of testing. I designed magazine ads. I was, by virtue of the fact that I lived closest to the office, the designated rebooter of the development server, regardless of the time of day (or night) it decided to act up. Having actually written several manuals, I suppose it made sense that if someone other than me was going to write the Reality manual, I should manage them. But this was TOM OBERHEIM. What if he didn’t want to be managed?

I need not have had any concerns about Tom. He is a very nice man. Not much of a tech writer, as it turns out. I ended up writing the manual anyway. But it was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted almost 30 years. (It’s not that Tom can’t write, but tech writing is not as easy as you might think. Just think of all the truly awful user documentation out there.)

Getting Suggestive

Have you ever been in a social or business situation where several people are actively contributing to the discourse and you’re waiting for just the right time to jump in and say something impactful, or even just clever? A charged opinion. A joke. A possible solution or clarification. A different perspective or direction.

As we neared the end of Prophet-6 development, Dave set aside time at the weekly staff meeting to discuss ideas for whatever the next product might be. Once we got to the point where most of the development effort was focused on squashing bugs and polishing an instrument for production, Dave would already be looking to the next thing. I don’t remember what other suggestions were offered, but I came armed with one that I’d already been thinking about for a while. The conversation was lively, as it often was on these occasions, but there was a brief lull, so I leapt at the opportunity. “What if we make an Oberheim-style synth using the Prophet-6 platform?” I was prepared to make my case, but there was no reaction at all. Not positive. Not negative. Nothing. It was as if I hadn’t said anything. And then the conversation resumed and moved on. I was very confused. Not only had my suggestion not landed, I was now worried about bringing it up again. On the plus side, Dave hadn’t actually said no, but if the idea didn’t even warrant consideration, was that just as bad? Worse? I had learned that if Dave nixed an idea and you wanted him to reconsider it, you had maybe one chance to argue its merits, and that argument needed to be not just compelling, but bullet proof. If he still said no, it was time to move on. But this was different and I wasn’t sure how to proceed.

Sometime not long after that, Dave, Tom, and Roger Linn were going to Sweetwater Music for an appearance of some sort. Joanne (DSI’s General Manager and my spouse) and I were in Dave’s office at the end of a workday talking about nothing in particular just before he and the others were due to be flown to Indiana on Sweetwater’s jet. So I said, “Why don’t you ask Tom about making an Oberheim version of the Prophet-6?” He asked what I had in mind, so I said, “We already did the SEM filter in the Pro 2, so Tony could make voice cards with that filter and we could change the panel layout and graphics to be more Oberheim-y.” Dave talked to Tom on the plane and that’s how the OB-6 got started.

I am aware that Dave’s version of this story is slightly different, mostly in that I’m not in it. I am totally fine with that. I could not be more fine with that. As the saying goes, never let the facts get in the way of a good story. I also do not want to give anyone the impression that I’m writing any of this to set the record straight or anything like that. My sole intent is to shine a light on Dave and to document what it was like to work with him and the DSI/Sequential team while I still remember it. I had a dream job and got to do it with almost total anonymity, free from any outside influence. How great is that? That is what Dave provided me. That and a buttload of cool synthesizers.

Those Fucking Lines

Tom and I had talked about synths over the years and, on several occasions, he remarked how often people asked him to remake the OB-X, perhaps because not many were made. Or maybe Rush/Tom Sawyer? I don’t know. What little I did know about the OB-X was that it had a (low-pass only) SEM filter, and we had already made a synth with an SEM filter in it. And our hardware engineer Tony Karavidas had worked at Oberheim and owned multiple Oberheim synths. I also felt very strongly that if we were going to make two poly synths that were essentially the same except for the filter, the 2-pole, SEM state-variable filter would be complementary to the Prophet-6’s 4-pole, OTA low-pass filter.

Tom’s wish list was short. He didn’t want the Prophet-6’s analog distortion. And he wanted the OB-Xa’s blue lines. (After the OB-6’s release, I was amused when some people compared the OB-6 to the OB-Xa or OB-8—based, I suppose, on the graphic design—and declared that they sounded very much the same. They don’t. I wouldn’t even say it’s close.)

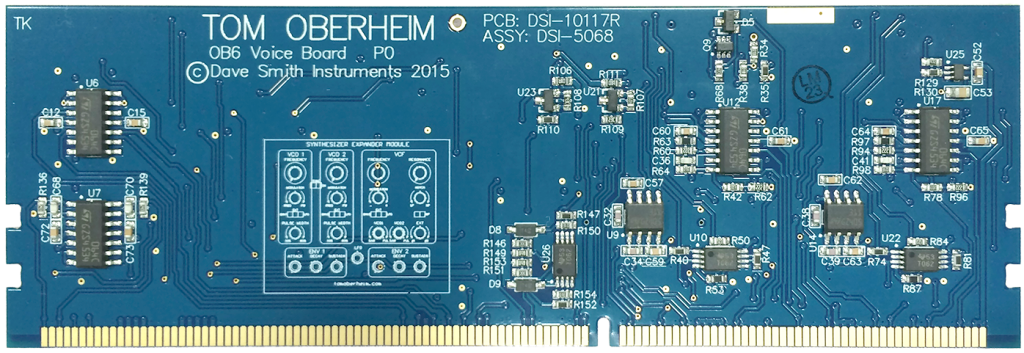

As I detailed in my Prophet-6 piece, we typically started a design by drawing the front panel and then designed everything else around that. For the OB-6 and, later, Trigon-6, we started with an existing design, the Prophet-6. On the positive side, that meant much of the electronic and mechanical work was already complete and tested. Tony’s primary focus was to create new voice boards with an SEM-based analog voice. The OB-6 main board is the Prophet-6 main board (which also meant that the analog distortion would be present, even if it was not accessible from the front panel).

On the negative side, I had to create a new panel layout inspired by the OB synths and make it fit in a predetermined amount of space. The Prophet-6’s resonant high-pass filter was gone, but the SEM state-variable added a couple of controls, Filter Mode was added as a modulation destination, and co-worker Carson Day had asked to add a destination to modulate between “normal” and band-pass modes.

What made it difficult was the blue lines, because the lines dictate where you can place things. Text has to go between the lines. Potentiometers and encoders go between the lines. LEDs mostly go between the lines, even though they don’t need to be spaced that far apart. A few of the LEDs are on the lines because there is text below them and the white text can’t overprint the blue, even if the white is printed after the blue. Switches are centered on the lines because they’re too big to fit between them. And because the lines effectively acted as a grid in one dimension, I had to keep monkeying around with the line spacing to make everything fit, which meant nudging things around by hundredths of an inch rather than snapping items to a grid as I would normally do. I think I went through more iterations of the OB-6 panel design than any of the other synths I worked on. I don’t remember for certain, but I think the final line spacing was 0.23″.

The other issue with the blue lines had to do with getting them on the synth. Our sheet metal vendor, who was doing all our screen printing at that time, took a hard pass upon seeing the artwork, saying it would cause production bottlenecks. I found a screen printer who would do it, but not without some trepidation on their part. Industrial screen printers are few and far between these days and most of their print work consists of printing a single color on relatively small objects, like rack panels and small metal enclosures and plates. A keyboard instrument with 3 colors is a complicated job, and the inks are epoxy-based, so if there is an inclusion (fuzz, lint, hair, etc) or a misalignment or smudge, the only recourse is to take the panel down to bare metal and repaint/reprint it or simply scrap it.

You might be thinking, they were able to do it in the ’80s, so why is it a problem now? Part of it is the lack of experienced screen printers, but if you have the opportunity to examine enough vintage instruments, you will see a fair amount of mediocre screen printing. I have seen several OBs with what I would consider to be poor screen printing by current standards. (I’m not picking on Oberheim. It’s true of other manufacturers’ synths, too, though the blue lines and the OB-X’s gray blocks and knocked-out text tend to amplify issues.) Screen printing is still done by hand and I’m not aware of any great technological advancements to counter screen stretching or misalignment. Maybe fixturing is better now, but there’s still a period of tweaking that happens in pre-production and, if I’m being honest, often continues into early production before the parts are of a consistently high quality. (Another reason not to be an early adopter.) That was definitely the case with the OB-6. The slightest rotation of the blue lines can be obvious to even untrained eyes. And if the blue lines are straight but the white layer is rotated slightly, the lines make that obvious, too.

I did experiment with digital printing for the OB-6, but—in 2015, at least—it was both more expensive and more logistically complicated than screen printing. That may be different now. I won’t go into the details here, but hit me up if you want to know more about the experience, or even if you want to tell me I’m old and out of touch and it’s gotten much better since then. I’m fairly thick skinned.

And Another Thing…

I intended this to be a brief companion piece to the Prophet-6 posts, but I seem incapable of brevity…

Tony’s work on the voice cards went quickly and they sounded great and showed just how much of a subtractive synth’s character is determined by the filter. The OB-6 sounds nothing like the Prophet-6. For me, the Prophet-6 is the more versatile of the two synths, while the OB-6 is capable of fizzier, more aggressive sounds that stand out, but don’t overwhelm (unless you want them to). I like them both very much.

The shape of the OB-6’s envelopes are based on the SEM and are significantly different from the Prophet-6.

The design of the OB-6’s custom knobs is based on the original skirted Oberheim knob (with the skirt removed) and is adapted from the design work that engineer Dick Yokota did for Tom on the TVS-PRO. Dick subsequently consulted on several of Sequential’s injection-molded plastic parts until his untimely death during the development of Take 5. He was a tremendous asset to me and DSI/Sequential. I can design in 3D, but I need help to translate those designs into manufacturable parts. Dick is solely responsible for devising the method of attaching the plastic end panels on the Pro 3, Take 5, and TEO-5.

When sound designer Drew Neumann got his preproduction OB-6, one of his first questions was, “Where’s the distortion?” It was added as a “hidden” feature. To this day, I regret that it does not have a dedicated panel control.

The OB-6 debuted at NAMM on January 21, 2016 and started shipping in March. It was cobranded as a Dave Smith Instruments/Tom Oberheim product. Some later OB-6s have Sequential, Oberheim, and Tom Oberheim logos on them, but the differences are purely superficial, not to mention somewhat confusing.

Trent Reznor had an OB-6 that sounded broken in a way that he liked—it may have just needed tuning—and inquired about getting a second one so as not to mess with the “broken” one.

The OB-6 desktop module sold in greater than usual numbers relative to the keyboard, though it’s difficult to know why. Maybe because people already had Prophet-6 keyboards?

Postscript: The OB-X8

Joanne is exceptionally fond of Tom and Jill Oberheim—as are we all—and was especially happy that the collaboration on the OB-6 was a success and paid a royalty to Tom. After the Prophet-5 rev 4 came out, she was lobbying Dave to do another collaboration. Our co-worker Mark Wilcox suggested doing a variation on the Oberheim 8 Voice. I offhandedly suggested something like, “We could do what we did with the rev 4 and make an OB-X that also has the Curtis filter in it,” not really understanding what that meant or where it would go once Marcus Ryle got involved.

Thanks to Marcus and the OB-X8, I now know a lot more about Oberheim synthesizers, but at the time, my experience was very limited. I had never laid hands on an SEM-based poly synth. (I still haven’t.) I don’t recall ever having played an OB-X, OB-Xa, or OB-8 before that. I played an original Two-Voice Synth (my personal favorite) back in Sequential Circuits days. I think I may have played T Lavitz’s OB-1 back then, too, but my memory is fuzzy. And I briefly owned a Matrix-1000, which I did not care for at all. I was renting a room in a small, two-bedroom, 1920s bungalow at the time and didn’t have much space, so a single rackspace poly synth seemed ideal. I bought it new, but it was plagued by annoying clicking/thumping noises. It’s entirely possible there was something wrong with it. I also hated using the editor. Lesson learned. Synth rejected.

Anyway, my point was that, if not for Joanne pestering Dave about making another instrument with/for Tom, and Dave’s affection for Joanne, there might not be an OB-X8.